< Back to Carpets

& Rugs

< Previous

Next >

The Baluch Rugs Weaving

"When creating the world, the Almighty made Beluchistan out of the refuse" are the words of an old proverb, that refers to the land which formerly produced some of the most interesting and exceptional rugs of the East. In fact the thought is not surprising when the desolate character of the country is considered - it is quite amazing to explore signs of cultivation in an area which has sandy, waterless waste stretches over its greater part, and where you can find water only in a corner to the northeast and in narrow stripes, where streams from mountain sides water small valleys. Across this sparsely settled land and farther westward into the southeastern part of Persia, untamed tribes of Beluches wander with their sheep, goats, and large numbers of camels.

Their rugs, woven on crudely made looms, bear little resemblance to the more artistic floral pieces of Indian weavers to the east or to those of Kirman to the west. Nor are they closely related to the Turkoman rugs with which they are usually grouped. In fact, they posses an individuality that once recognized is never forgotten; an individuality due to the isolated condition of the county and the fact that their rugs are rarely colored with aniline dyes.

One of the most distinguishing feature of the Beluchistans are their tones of color, that rarely depart from traditional usage - principally a red of the shade of madder, a blue with purple cast, and a dark brown that has sometimes a slight olive tinge. Contrasting with these more subdued ground colors is almost invariably some ivory / white which usually appears as small detached figures in part of the border, or as outlines of the principal designs.

History and Origin of the Baluch Tribes

Our knowledge concerning the history and the

origin of the

Baluch is lacking. According to linguistic studies, the

Baluch language is a separate Indo-European language with relations to

the Middle Persian, the Kurdish and the Parthian languages. These findings indicate that

the origin of the Baluch is in the area between the south of the

Caspian Sea

and Armenia

and that their ethnic roots are distinguished from the ethnic roots of the majority of the oriental Turkmen

tribes such as the Tekke, Yomut and Salor.

The name Baluch appears in historical sources for the first time, as the

name of nomad groups in the area of

Kerman, which

was conquered by the Arabs in the 7th century. At the end of the 10th century, in

response to the expansion of the

Seljuks,

the Baluch began to spread into

Khorassan and

Sistan, a move which triggered counter attacks by the local Moslem tribes.

This in turn,

caused the Baluch heavy losses and forced them to retreat southwards

into the area which is known today as

Baluchestan va Sistan.

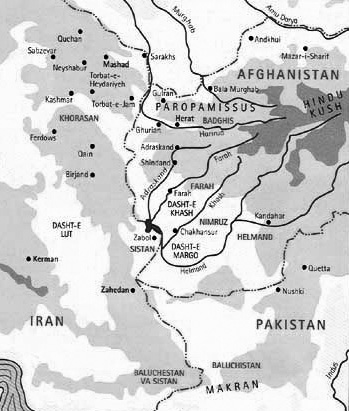

A map of the Baluch dispersion near the border between Afghanistan, Iran and Pakistan

During the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries, groups of eastern Baluch spread into the west and south areas of Afghanistan. In the east, their numbers diminished gradually in a zone, which goes roughly from Quetta in today's Pakistan, to the Amu Darya River in northeast of Afghanistan. Single clans settled in northwest Pakistan, India, and even in the western part of Chinese Turkestan. This wide population dispersion is probably one of the reasons why the Baluch never formed influential political organizations such as those of the Turkmens. The lack of central organization and unity led to fierce internal battles between the Baluch's sub-tribes, which went on for years and further weakened the Baluch's ability to keep their independence as a minority ethnic group.

The Baluch Weaving Culture

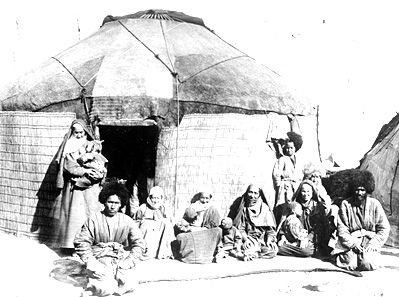

The dominancy of the Turkmen tribes who have outnumbered the Baluch by far, and who have been very conscious of their own weaving traditions and religion, caused the Baluch to adopt the Turkmen pile rug weaving techniques and symbolism. Nevertheless, most Baluch groups have succeeded to keep their original traditions in spite of the aggressive pressure of their neighbors, and preserved their own language and tribal family structure, their unique artistic patterns as well as the form of their tents which differed from the Turkmen's Yurt.

A typical Baluch tent

A typical Turkmen Yurt tent

It is agreed today that the weavers of the rugs we call Baluch were actually comprised of several tens of dynamic and mobile nomad groups of weavers which existed in the margins of ecological niches in the areas of south-western Pakistan, south-eastern Iran, and the border lands between Iran and Afghanistan, all the way up to southern Turkmenistan as described in the map above. These groups were constantly forming new social and economical units which succeeded to survive alongside the strong Turkmen tribes due to their excellent weaving skills. Although in recent years the strengthening of the government authority in Afghanistan, Pakistan, and especially in Persian Khorassan has limited the freedom and mobility of the Baluch, it is still difficult to identify specific clans and consistently ascribe a type of Baluch rug to one specific group as we can do with the Yomut or Tekke Turkmen rugs. It seems more practical to classify Baluch rugs and weaving patterns according to the geographical regions in which they were most often found, or to group them by their design and/or technical features.

As is the case for all Turkmen tribes, the Baluch rugs were made by female weavers, who used horizontal, collapsible wooden looms. Due to the nomadic way of life, a not yet finished piece of rug was rolled around the warp beams of the disassembled frame when the group moved on to another pasture.

Sheep's wool and more rarely camel wool were used for the pile. Sometimes silk was also used but, due to its price, only to accentuate certain colors that were not easily obtained in wool with natural dyes, e.g. green and purple. Recipes for the production of plant and stone dyes were kept secret among the weavers families and not revealed even within the clan.

Until the middle of the 20th century, pile-weave and flat-weave fabrics were mainly made for the Baluch own use. New pile rugs were part of the standard dowry and served to prove the weaving skills of the bride. In addition, due to the structure of the Balouch tent, which was more vulnerable to weather ravages and did not offer as much protection as the Turkoman's yurt, rugs wore out rapidly and thus had to be replaced more often. This also explains why older or even semi-antique pieces were rarely found among the Balouch themselves. During good years a Balouch family would weave one or two additional rugs which were sold in the nearest city bazaars or exchanged for utensils, tea, sugar, cotton cloth etc.

Typical Types of Baluch Rugs (measures in cm):

- Ghali - tent rug, often flat-weave, 115-215 x 230-350

- Ghalitshe - floor and tent rug, pile-weave, 85-127 x 140-226

- Germetsh - small tent rug, pile-weave, 65-75 x 120-130

- Dja-Namaz - prayer rug, pile-weave, 75-110 x 90-260

- Daliz - runner, pile weave, 110-125 x 250-480

- Sofre - tablecloth, flat-weave with pile-weave parts, 80-100 x 150-200

- Korssi-Dane (Ru-korssi) - korssi cover, flat weave with pile-weave parts, 120-130 x 120-130

- Poshti - back pillow, pile-weave mostly made in pairs, 65-75 x 85-95

- Balisht - head pillow, pile-weave usually made in oblong format, 40-50 x 65-107

- Khordjin - big saddle bags, pile-weave made in pairs, 65-95 x 68-98

- Khordjin - small saddle bags, pile-weave made in pairs, 35-55 x 50-60

- Torbak - small belt purse and shoulder-strap bag, pile-weave, 23-30 x 20-30

-

Sine Asp

- saddle blanket for horses, pile-weave, 45-80 x 60-65

Tent Rugs

The types and size of the Baluch rugs were customized according to the structure and dimensions of the Balouch tent and according to the needs of the Baluch nomadic way of life. During the day, the Baluch tent's floor was covered with simple dark, coarse and shabby felt mats, made of goat's hair which could no longer be used for the roof of the tent. When visitors came, as well as at night time, the Baluch domestic pile rugs were spread on top of the mats. The size of these "sleeping rugs" which were also used to sleep on when travelling, were customized and differed from the Turkoman's hearth rug the Odjaq Bashi. The Balouch also made a smaller size rug, which is similar to the Turkoman Germetsh or Dahanghi, and served as a doorstep rug at the entrance to the tent.

Larger pile rugs were very rare and were found only in the Baluch clans around Herat and in the south, near the Afghan Pakistani border. Flat-weave rugs of large size were found only in the Iranian Baluch groups, so with the exception of these large formats, the Iranian and Afghan Balouch used about the same size rugs for the same purposes. This also applies to the Baluch prayer rugs, which were a little bit smaller and constituted a category of their own. Some Balouch families that became sedentary, wove Daliz - runners which were suitable for their permanent dwellings.

Pillows

The head pillow, Balisht or Bolest, with pile-woven front is a specific Balouch product which was not woven by the Turkomans. The Balisht format is quite similar to the small Turkoman Torba tent bags, but they are opened only at the upper small side from where they were stuffed with raw cotton and then sewn up. Both sides of the Baluch Bolesht may have carefully ornamented web-ends.

If the flat-woven back part of the Balisht is lost then it is quite difficult to identify the original function of the rug. This is one of the reasons why Turkmen's Torbas were incorrectly classified as a Bolesht. The square back pillows, Poshti, with pile-woven fronts are also a typical product of the Balouch and their formats are similar to the Turkmen big saddle bags but they are, however, more finely knotted and do not have clasping ledge closure systems.

Saddle Bags & General Purpose Bags

Small and big saddle bags, Khordjin, with pile woven fronts were also produced by the Baluch. The Afghan Balouch weavers preferred bigger sizes decorated with colorful tassels and shells which they found in the deserts of south Afghanistan. Most Poshti and Khordjin were made in pairs with a single warp thread. The weaving work started at the upper end of the knotted front side of the first bag. The clasping ledge was added later with loops made of black goat's hair and then follows a flat-woven part, consisting of the back part of the first bag, a 30-40 cm wide bridge, and the back part of the second bag. The work was then continued with another pile-woven part for the front of the second bag. The weaving was finished at the upper end of the second bag. The knotted front sides were then turned over towards the bridge onto their flat-woven back sides and selvaged together. This weaving technique caused the pile of the two bags to be oriented in opposite directions. In some Baluch bags from Afghanistan, both front pieces are connected over the bridge at their long sides with small knotted strips, which continue the pattern of the borders. Thus the center part of the bridge looks like a window in the pile-woven frame. There are also pairs of bags whose back parts and their bridges are flat-woven sometimes with stripe patterns and colorful zig-zag designs.

The Baluch also made a small pile-woven bag called Chanteh which have loops on the back side to pull a belt or a shoulder strap through. Islamic wandering monks in central and north Khorassan used them as purses. Finally, there are the pile-woven gun cases, which the Balouch made until the beginning of the 20th century and were intended to protect the barrel and lock of the gun against sandstorms. They were sewn together from two equally long strips.

Types of Rugs which were not produced by the Baluch

The Baluch did not have any big oblong shaped tent bags

similar to the Turkmens Juval or Chuval or Doshak. They neither have knotted

spoon, comb, or mirror cases, nor something equivalent to Turkomans' Ok

Bashi - a protective cap

that was pulled over the ends of the bundled up tent poles. They hardly made any

salt containers, which were more common among the Tshahar (Chahar)

Aimaq.

Pile rug fabrics as decoration for use on riding animals were almost limited to

saddle blankets. Festive head-gears were rarely made. Non-nomad Balouch used,

however, coarsely knotted strips as harness for donkeys. Caparisons, as seem

among Yomud Turkomans, have not been found among the Baluch. Likewise, there are no decorative

trappings for wedding camels, like the Turkmen Djollar, Asmalyk, and

Diah Disluk: the Balouch bride usually rode a horse with the

exception of the south Afghan Beluchi who had headdress for camels which was made of pile-woven strips and upright tassels.

Since the structure of the Balouch tent

did not included tent bands, elements such as the Turkmen Tang, Nawar

and Yolami, the Kapunuk frames for the entrance and entrance rugs

such as the Ensi, Khatshlu and the Tshahar Fazl, were not

part of the Balouch weaving products.

Typical Baluch Weaving Colors

The Baluch weavers used natural dyes much longer than the Turkoman weavers. The important traditional colors of the Baluch field and borders are as follows:

- Dark blue to black blue (made with very concentrated indigo)

- Medium blue (weaker concentration of indigo)

- Brick red, fire red to dark red (made from madder of different ages)

- Aubergine shades (old madder with additional dyes)

- Camel brown (un-dyed camel wool)

- White to cream-colored (un-dyed, sometimes bleached sheep's wool)

- Black brown (natural wool with additional dyes, e.g. walnut shells)

In many Balouch rugs the ground color in the border(s) is the same as the one in the field. If the center field is, however, camel brown, red tints are usually used in the borders. Red borders can also frame a dark blue field. A reverse color combination was not seen in older rugs.

Different shades of ground colors are frequently used for field motifs. When red

tints are used the design is still discernable but when

dark blue is used on dark brown, like in many very finely knotted saddle bags

made by south Afghan Balouch, it is sometimes hard to distinguish the

design details if not in full daylight. Details in motifs, like small petals, as well as

outlining strips are very often white and/or yellow or yellow orange. Green was

used in older carpets only sparingly. Darker tints are seen in older rugs from Sistan and Afghanistan. Lighter blue colors were often found in rugs from

central and north Khorassan. Very often motifs were set off with black bordering

lines.

Have a question or comment? - Call

Despite all that has been written about the Baluch pile weaving groups that inhabited the tough areas of northeastern Iran and western Afghanistan, it seems that the tribal affiliations and artistic approach of the weavers described by the catch-all term "Baluch" still remain open to questions. Nevertheless, for me, such a mystery in no way discourages the fascination that I have for these dark and mysterious weavings created by the Baluchi nomadic and village women. I'll be happy to receive and publish your comments and remarks - thanks.

מבין קבוצות

אורגי השטיחים הנוודים שחיו במאה ה-19 ותחילת המאה ה-20 במרחב קשה הקיום שבין

צפון-מזרח פרס למערב אפגניסטאן, זו המכונה בלוץ' או בלוצ'י היא האהובה עלי. קראתי

רבות על אי הבהירות שבהגדרת ההשתייכות השבטית של הבלוצ'ים ועל כך שמוצאם שונה מזה

של השבטים הטורקמנים. הבלוצ'ים ברוכי הכשרון נאלצו לשרוד כמיעוט חלש ומפוצל תחת

"חסותם" של שכנים טורקמנים חזקים כמו הטקה, היומוט, הארסרי, הסלור והסאריק ויש

אומרים שלמעשה נטמעו בהם. רבות נכתב גם על השפעת המוטיבים הטורקמנים על תרבות

האריגה הבלוצ'ית הייחודית והאם זה נעשה בכפייה או לא, אבל למרות השאלות הרבות

שנותרו פתוחות בעניין, איני יכול לעמוד בפני הקסם של השטיחים הכהים והמסתוריים

שארגו הנשים הבלוצ'יות המוכשרות כל כך בתנאים לא תנאים. ניסיתי לרכז בדף זה מעט מן

המידע הנפוץ בחוגי אספני השטיחים הטורקמנים בקשר למוצרי האריגה של הבלוץ' ובעיקר

התבססתי על מחקרו של ד"ר דיטריך ווגנר משנת 1985. אשמח לקבל ולפרסם תגובות, הערות

ותיקונים.

***

References:

Pile Rugs of The

Baluch and Their Neighbors - Dr. Dietrich H. G. Wegner

Turkmen Rugs - Terminology, Transcription, Pronunciation, Spelling and

Nomenclature

© Dan Levy - Art Pane Home of Oriental Carpets and Rugs

< Back to Carpets

& Rugs

< Previous

Next >